Fundamentals of Cryptography

Introduction

Cryptography can seem complex, but a lot of cryptography boils down to some very simple mathematical operators and structures. In this article, we talk about some of the most commonly used functions and structures used in cryptography.

The mathematics of cryptography

Under the hood, cryptography is all mathematics. For many of the algorithms in development today, you need to understand some fairly advanced mathematical concepts to understand how the algorithms work.

That being said, many cryptographic algorithms in common use today are based on very simple cryptographic operations. Three common cryptographic functions that show up across cryptography are the modulo operator, exclusive-or/XOR and bitwise shifts/rotations.

The modulo operator

You’re probably familiar with the modulo operator even if you’ve never heard of it by that name. When first learning division, you probably learned about dividends, divisors, quotients and remainders.

When we say X modulo Y or X (mod Y) or X % Y, we want the remainder after dividing X by Y. This is useful in cryptography, since it ensures that a number stays within a certain range of values (between 0 and Y – 1).

Exclusive-or

In English, when we say OR, we are usually using the inclusive or. Saying that you want A or B probably means that you’re willing to accept A, B or both A and B.

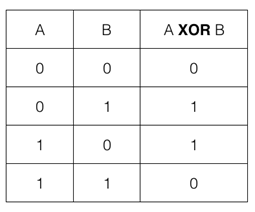

Cryptography uses the exclusive or where A XOR B equals A or B but not both. The image above shows a truth table for XOR. Notice that anything XOR itself is zero, and anything XOR zero is itself.

XOR is also useful in cryptography because it is equivalent to addition modulo 2. 1 + 0 = 1 and 1 + 1 = 2 = 0 (mod 2) = 0 + 0. XOR is one of the most commonly-used mathematical operators in cryptography.

Bitwise shifts

A bitwise shift is exactly what it sounds like: a string of bits is shifted so many places to the left or right. In cryptography, this shift is usually a rotation, meaning that anything that “falls off” one end of the string moves around to the other.

The bitwise shift is another operator that has special meaning in modulo 2. In binary (mod 2), shifting to the left is multiplying by a power of two, while shifting to the right is division by a power of two.

Common structures in cryptography

While cryptographic algorithms within a “family” can be similar, most cryptographic algorithms are very different. However, some cryptographic structures exist that show up in multiple different cryptographic “families.”

Encryption operations and key schedules

Many symmetric encryption algorithms are actually two different algorithms that are put together to achieve the goal of encrypting the plaintext. One of these algorithms implements the key schedule, while the other performs the encryption operations.

In symmetric cryptography, both the sender and the recipient have a shared secret key. However, this key is often too short to be used for the complete encryption process since many algorithms have multiple rounds. A key schedule is designed to take the shared secret as a seed and use it to create a set of round keys, which are then fed into the algorithm that actually performs the encryption.

The other half of the encryption algorithm is the part that converts the plaintext to a ciphertext. This is typically accomplished by using multiple iterations or “rounds” of the same set of encryption operations. Each round takes a round key from the key schedule as input, meaning that the operations performed in each round are different.

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is a classic example of an encryption algorithm with separate parts implementing the encryption operations and key schedule, as shown above. The different variants of AES (AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256) all have a similar encryption process (with different number of rounds) but have different key schedules to convert the various key lengths to 128-bit round keys.

Feistel networks

A Feistel network is a cryptographic structure designed to allow the same algorithm to perform both encryption and decryption. The only difference between the two processes is the order in which round keys are used.

An example of a Feistel network is shown in the image above. Notice that in each round, only the left half of the input is transformed and the two halves switch sides at the end of each round. This structure is essential to making the Feistel network reversible.

Looking at the first round (of both encryption and decryption), we see that the right side of the input and the round key are used as inputs to the Feistel function, F, to produce a value that is XORed with the left side of the input. This is significant because the output of F in the last round of encryption and the first round of encryption are the exact same. Both use the same round key and same value of Ln+1 as input.

This means that the input to the last round of encryption is XORed with the same value twice, and these two operations cancel one another out (anything XOR itself is 0 and anything XOR 0 is itself). Continuing this process, the second round of encryption undoes the second-to-last round of encryption and so on. The result of decryption is the original plaintext.

Feistel networks are useful when implementing cryptographic algorithms in hardware. The ability to use the same operations for encryption and decryption means that chip designers only have to do half as much work.

Beyond the basics

An understanding of the functions and structures discussed here — as well as common mathematical functions like multiplication, division, exponents and logarithms — is enough to understand a large chunk of the cryptographic algorithms out there. If you want to get into cryptography that uses more complicated math, check out the post-quantum algorithms currently under development.

Sources

- XOR and XNOR logic gate, dyclassroom.com

- Why do Feistel ciphers need round keys, crypto.stackexchange.com