Tutorial for Building and Reverse Engineering Simple Virtual Machine Protection

1. Introduction

The virtual machine protection refers to the kind of software protection technology by which the original executable and readable code are translated into a string of pseudo-code byte stream, and a virtual machine is embedded into the program to interpret and execute that pseudo-code byte stream. The difference between virtual machine protection technology and the other virtual machine technology, such as Java Virtual Machine, is that virtual machine protection technology is designed for software protection and uses a custom instruction set.

There are some famous commercial virtual machine protection products, such as VMProtect, Themida, etc., but all of them are too complex to analyze. To illustrate the software protection technology, we turn to build a simple virtual machine project. Although this project is far from the commercial products, it is enough for building a CrackMe.

FREE role-guided training plans

By the way, GitHub is a fantastic site, and we have found a perfect source code written by NWMonster. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: the CrackMe built by NWMonster's source code is reverse engineered in section 2, and source code is introduced in section 3, and we summarize this paper in section 4.

2. Reverse Analysis

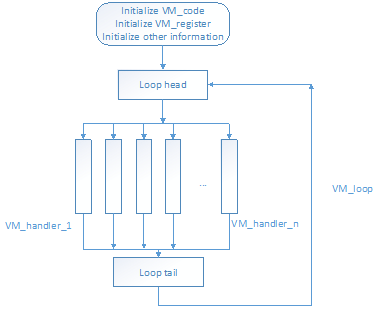

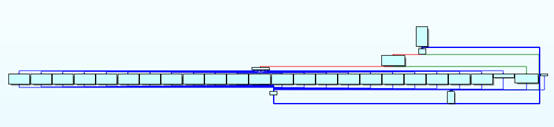

Before we reverse engineer this CrackMe, there are something that we need to understand. The flowchart of a simple virtual machine protection is shown in the following figure:

In this figure, VM_code represents the pseudo-code byte stream, and VM_register simulates the general registers of CPU. In the one run of VM_loop, the virtual machine will run the specific VM_handler according to the VM_code read in Loop head. To reverse engineer a simple virtual machine protection, we need to figure out the meaning of every VM_handler, and thus grasp the main idea of the origin program, which is protected by the virtual machine.

Pay attention that this flowchart does NOT apply to commercial virtual machine protection products because this flowchart is too simple.

From now on, let's begin our reverse engineering. Usually, OllyDbg (OD) is used to trace out the VM_loop, but this time we use IDA because the graphic view of IDA is much clearer. To make it easy for our discussion, we rebuild the source code to run in x86 Windows environment with debug version. All the materials will be uploaded to GitHub for the readers who need them.

After putting this CrackMe into IDA, it is easy to find out the 207 bytes VM_code in the CrackMe:

In addition, VM_code in the above figure is assigned to [eax + 20h]:

From those instructions, we can assume that EAX points to VM_register structure and EAX+20h points to IP register, like this:

+0x00 ??

+0x04 ??

+0x08 ??

+0x0C ??

+0x10 ??

+0x14 ??

+0x18 ??

+0x1C ??

+0x20 IP register

}

The VM_loop can be found just after VM_register initialization:

By counting the squares in the figure, it seems that there are totally 23 VM_handlers in this virtual machine. Now, we need to analyze those VM_handlers in the order of VM_code sequence. The first byte of VM_code is 0xDE, which corresponds to VM_handler_defaultcase:

The detail of VM_handler_defaultcase is:

Notice that VM_register is the first element of VM class, so the another 0x4 offset is added to the origin 0x20 offset, which means *(this + 0x24) point to IP register in the VM_register:

+0x00 point to virtual table

+0x04 VM_register + 0x20 IP register

…

}

Now, we can see that VM_handler_defaultcase does nothing but increase the IP register. The second, third and fourth byte of VM_code also corresponds to VM_handler_defaultcase. To make it more comprehensive, we can rewrite VM_code as:

2 0xAD NOP

3 0xC0 NOP

4 0xDE NOP

The fifth byte of VM_code is 0x7C, which leads to VM_handler_22, and the detail of VM_handler_22 is:

From this figure, we can understand that VM_handler_22 XORs the following 0xF bytes VM_code with 0x66:

Currently, we cannot tell why those bytes are XORed with 0x66. The 21st VM_code is 0x70, which makes the virtual machine run to VM_handler_10, and the detail of VM_handler_10 is:

This is a typical PUSH stack operations, which pushes the next 4 bytes VM_code into VM_stack. It is equals to:

Besides, *(this + 0x20) seems to point to the SP register, thus, we can find another element in VM_register structure:

+0x00 ??

+0x04 ??

+0x08 ??

+0x0C ??

+0x10 ??

+0x14 ??

+0x18 ??

+0x1C SP register

+0x20 IP register

}

Until now, we have figured out the 25 bytes of VM_code, three handlers of VM_handler and part of VM_register. The whole analysis is too long to post here so that we leave the rest work for the readers to analyze by themselves. Anyone who is interested can check yourself by reading the source and the whole algorithm, which is protected by that simple virtual machine, is translated into CPP-file in the corresponding GitHub.

3. Build a simple virtual machine

With that source code in hand, it is rather easy to build a simple virtual machine. Let us first into that source code. The VM_register is defined as:

Where 'cf' is condition flag, and '*db' points to user-input data. The VM_loop is achieved by a while-switch structure:

Where 'r.ip' points to the VM_code. Moreover, VM_code is defined as an array of unsigned char:

The VM_handler is defined in the VM class:

As we can see, the first element of VM class is a REG structure, which is what we called VM_register structure; all the 23 VM_handlers can be found in the VM class. In the one run of VM_loop, the VM_code is read, and one of those VM_handlers is chosen to be executed.

Based on those source codes, we can easily build a simple virtual machine for ourselves. To make it easy, we use the existing VM_handler and VM_register. One can define more and obscure VM_handlers to make the virtual machine more difficult to analyze.

All we need to do is to design the sequence of VM_code to accomplish our purpose. For example, if we want to check out whether the 0x27 bytes user-input is a hexadecimal number or not, we can use the follow VM_code listed below:

POP, 0x30,

MOVD, 0x00, //loop begin

XOR, 0x22,

CMP, 0x02,

JZ, 0x33,

INCD,

PUSHD, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x46,

POP, 0x10,

CMP, 0x01,

JG, 0x27, //error user-input < 'F' ascII:0x46

PUSHD, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x30,

POP, 0x10,

CMP, 0x01,

JL, 0x16, //error user-input > '0' ascII:0x30

PUSHD, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x39,

POP, 0x10,

CMP, 0x01,

JL, 0x0b, //correct user-input < '9' ascII:0x39

PUSHD, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x41,

POP, 0x01,

CMP, 0x01,

JL, 0x06, //error user-input < 'A' ascII:0x41

XOR, 0x00,

CMP, 0x00,

JZ, 0x03,

XOR, 0x00, //error out R0 = 0

END,

LOOP, 0x3E, //loop end

XOR, 0x00, //correct out R0 = 1

INC, 0x00,

END,

The above code is taken modified from the origin source code. In the above list, each byte of 0x27 bytes user-input is compared with char 'F', '0', '9', 'A' to determine whether it is a hexadecimal number. If all the user-input are hexadecimal numbers, this virtual machine will leave with R0=1; otherwise, R0=0.

As soon as we finish writing VM_code, we need to replace the origin code with this VM_code, put them into practice and make sure that there is no bug.

4. Summary

In this paper, we reverse engineer a simple open source virtual machine protected CrackMe and build a simple virtual machine protection for ourselves. To reverse engineer a simple virtual machine protection, the key step is to find out all VM_handlers and understand the meaning of each VM_handler. When building a simple virtual machine protection, we need to design the sequence of VM_code to accomplish our purpose.

Besides, we have found some other virtual machine protected CrackMe from bbs.pediy.com, and we leave them for readers who are interested in reverse engineering them. All the materials mentioned above are uploaded to GitHub:

FREE role-guided training plans